ARTFUL

MEMORIES

︎︎︎︎︎︎

The ‘artist’ of the family

I was born in Glasgow Rottenrow Maternity hospital and by all accounts, it was ‘touch n go’. The result of which produced the perfect consumptive constitution conducive to creativity.Aged four, having to shelter from the cold Scottish sea air, I was ‘spotted’ in the Hotel by an elderly woman, who pronounced to my parents that they must be responsible for ensuring my continuation in the field of painting. Thus, the ‘artist’ of the family was proclaimed. Finding the pleasure of my own company by painting snowscapes etc. by streetlight at night from the window, I was hooked. Winning art competitions at school served as further encouragement.

In retrospect, what was already working for me was an abstract approach to dividing up the picture plane, alongside a strong response to materials, and I remember most of the paintings to this day.

By nine, I recall sitting on a garage roof, held by the feet in the gutter, and deciding that my life must include four aspects: the pursuit of something that

a. could be completely my own and that I could do independently,

b. would ensure an awareness of the present

c. allowed for collecting endless experiences, enabling me to die tomorrow without the sense of regret.

d. I could have as a focal point without ever having to retire. ART.

Unfortunately, this type of great clarity of thought began to dissipate with the confusion of adolescence, moving on to what I would term to be ‘a late developer’ in many aspects of adulthood. At 10 and 11, I had the privilege of attending weekend classes at the beautiful Glasgow school of art, feeling that with my gigantic black portfolio, I was well on the way to becoming a ‘real’ artist, as all the undergraduates appeared to me. The encouragement for freedom of approach to painting was thrilling, and I am forever nostalgic for living outside of time in my place by the enormous studio window. Naturally, I was heading only in one direction: a degree course in fine art.

︎︎︎︎︎︎

New discoveries

London, was ‘getting away’ and therefore I applied to do foundation at ‘Sir John Cass’, where at the interview, one of the tutors told me that I didn’t have ‘the character of a painter’ and then proceeded to ask me out! All the fields of art that year excited me, even though I decided to apply to do fine art at St Martins. After all, I had always been a painter!This time, apparently I was selected as one of the 5 women amongst 31 men in the 1975 year group, due to which seat (the table) that I chose to perch on during the interview, oh and for my interesting shoes! The fact that I told them that I had chosen St Martins due to its position in Soho and because I perceived that the course was not structured, was largely ignored.

The following three years, with time and grant money to completely immerse in ’the world of painting’, was heaven. To paint in an environment, alongside others’ creative energy was to have a lasting affect. However, for two years I flayed around, a sponge to the multitude of art that was being exhibited in London, and furious that I was ‘supposed to have found my style’ in the first year, when I didn’t even know the great heroes perceived by the college at the time; the mainly American, Abstract Expressionists.

︎︎︎

40 years and 100’s of series later, my method remains rooted in the same approach to making a painting.

40 years and 100’s of series later, my method remains rooted in the same approach to making a painting.

Then in the 3rd year, there came a ‘Eureka’ moment. I was painting the ceiling of my attic (of course) bedroom with emulsion and a much used paint roller. The resulting marks created by the rollers edge animated the ceiling in a way that prompted me to stretch a canvas onto the surface, to utilise this method further. On completion, I went to announce to my sister that I had made the best painting in my life and that I now knew what process I needed to follow. Even though she looked at me as though I was deranged, there was no going back. My degree show consisted of many of these 6×9 feet hangings, composed as a series in an effort to ‘exhaust’ the extent of work that the particular process could result in.

40 years and 100’s of series later, my method remains rooted in the same approach to making a painting. The basis being, that of needing to have and trust, thereby nourishing, a true response to the picture plane. The start must arise out of an overwhelming need to utilise certain materials on a chosen surface. From there, there must be a ‘conversation’; a feedback, from the first mark made to the self, as to what to do next. This ‘claim’ made by the work, must be persistent over any given time. Thus, my belief in The Abstract as the way for me to go, became the basis of my research.

However, as certain as it felt, my doubts lay in my inexperience and part of my many years of practice has been in validating for myself, why this particular approach had any sense to it. I began to develop my eye to see everything around me in abstract terms of line, form, plane, edge, texture, tone and colour. In regards to the latter, there was a moment in 1979, as I came out into a grey January afternoon from the ICA to The Mall in London, when I relished the tonal monochrome environment, to the extent that I realised that I felt ‘angry” with colour!

︎︎︎︎︎︎

Uncommon offers refused

After the end of college, a so-called ‘ coup’ happened to me, to which I was to a large extent oblivious. Many of the most eminent British artists of the time were invited by The Whitechapel Gallery to select their favourite painting from anywhere and by anyone in the world. Henry Mundy, who had been one of my tutors, and like the rest, I had refused any direction from, selected one of my 6×12 foot hangings to be placed alongside such eminence, as to appear as a joke!As a result, I was overwhelmed with gallery offers and positive reviews, one of which stated that I was the artist to launch the ’80’s’. There were only 2 problems; 1. a great fear of losing my heartfelt method of response for building a picture, to the weight of public opinion and 2. my naivety in recognising that such an opportunity was not common! Therefore, I refused all offers, with the rebuff, ‘that I was not making work like that any longer’!

︎︎︎︎︎︎

The perfect antidote

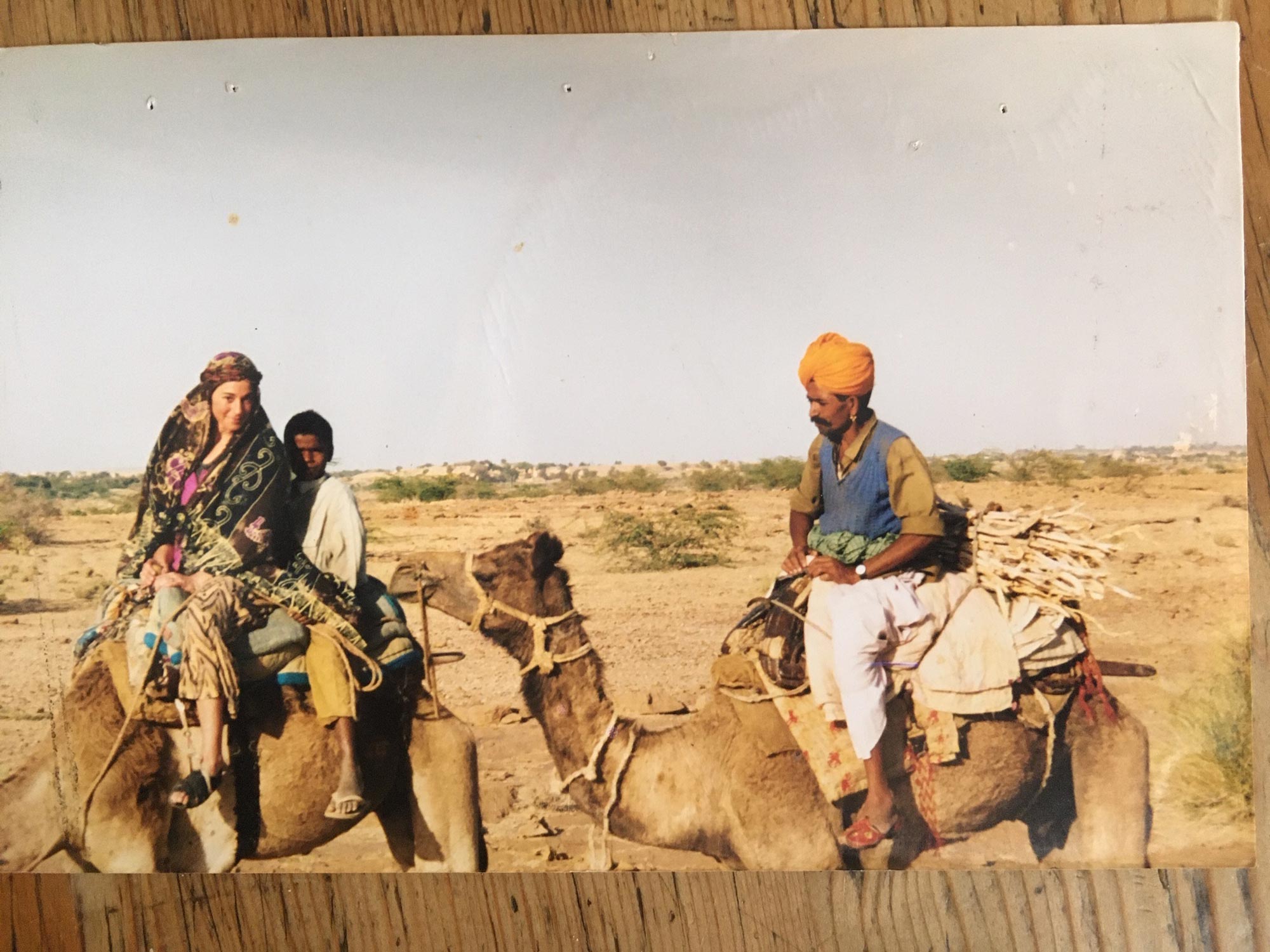

I began work as a waitress in a restaurant in Kings Rd., which was the perfect evening social and money making antidote to life in the studio all day. My workspaces tended to be enormous semi-official squatted warehouses, mostly on The Thames. In 13 years I lived and made work in 13 different places in London, where I relished moving to the next, as it always prompted a new and fresh series of works, in response to the environment. My pay was so good and my outgoings so minimal, that most years I could save half my income from 6 months, to facilitate being in India for the remaining 6 months of the year. Moving around with a small suitcase, I had the daily practice of dividing a wonderful handmade paper into 16 and completing a group for that day, in the knowledge that by the final piece, I would be as succinct as possible. Right up to the present, I am seduced in India by the colours, smells, and sounds to the extent that the resulting artwork is probably my least considered and successful!︎︎︎︎︎︎

The theatre gene

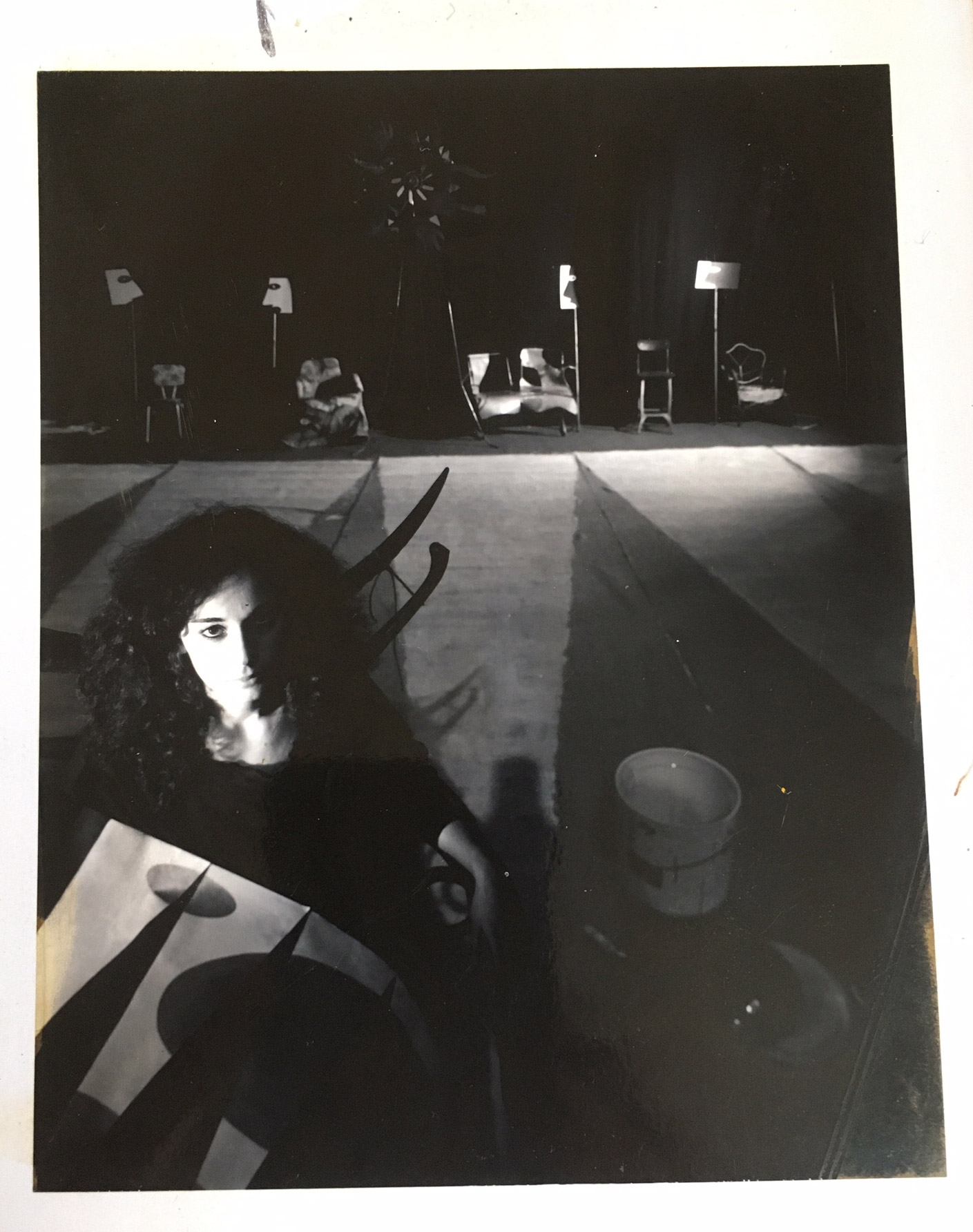

Over the years, I was offered shows, and in 1983(?)I was exhibiting at the Riverside Studios, when Benjamin Rhodes gallery invited me to open their new space with my work. After several years of being very well ‘looked after’, I, nonetheless and some may say rashly, left The Gallery, again assailed by doubts as to whether being in such a system, resulted in the struggle to retain the integrity of my approach. During that time, I attended a theatre production by the polish director, Tadeuz Kantor and although I had little comprehension of what was going on, I was smitten and bitten by Theatre of The Absurd.

Sometime after inside a house built by Alistair Crowley I found a copy of a play “Desire Caught By The Tail’ written by Pablo Picasso. My impulse was to create a ‘storyboard’, which I then took to the Riverside Studios to ask whether they would be happy for my actor friends to perform in their gallery. They gave me the 400 seat theatre for 3 nights, which had a full house, due to the publicity which spoke about the fact that the production had only ever been performed in the 50’s by Camus and Satre in the South of France. I happened to be ‘looking after’ Lord Gowry, the minister of cultures’ mansion in Holland Park, where we could rehearse, until in the middle of one night, the ceiling collapsed.

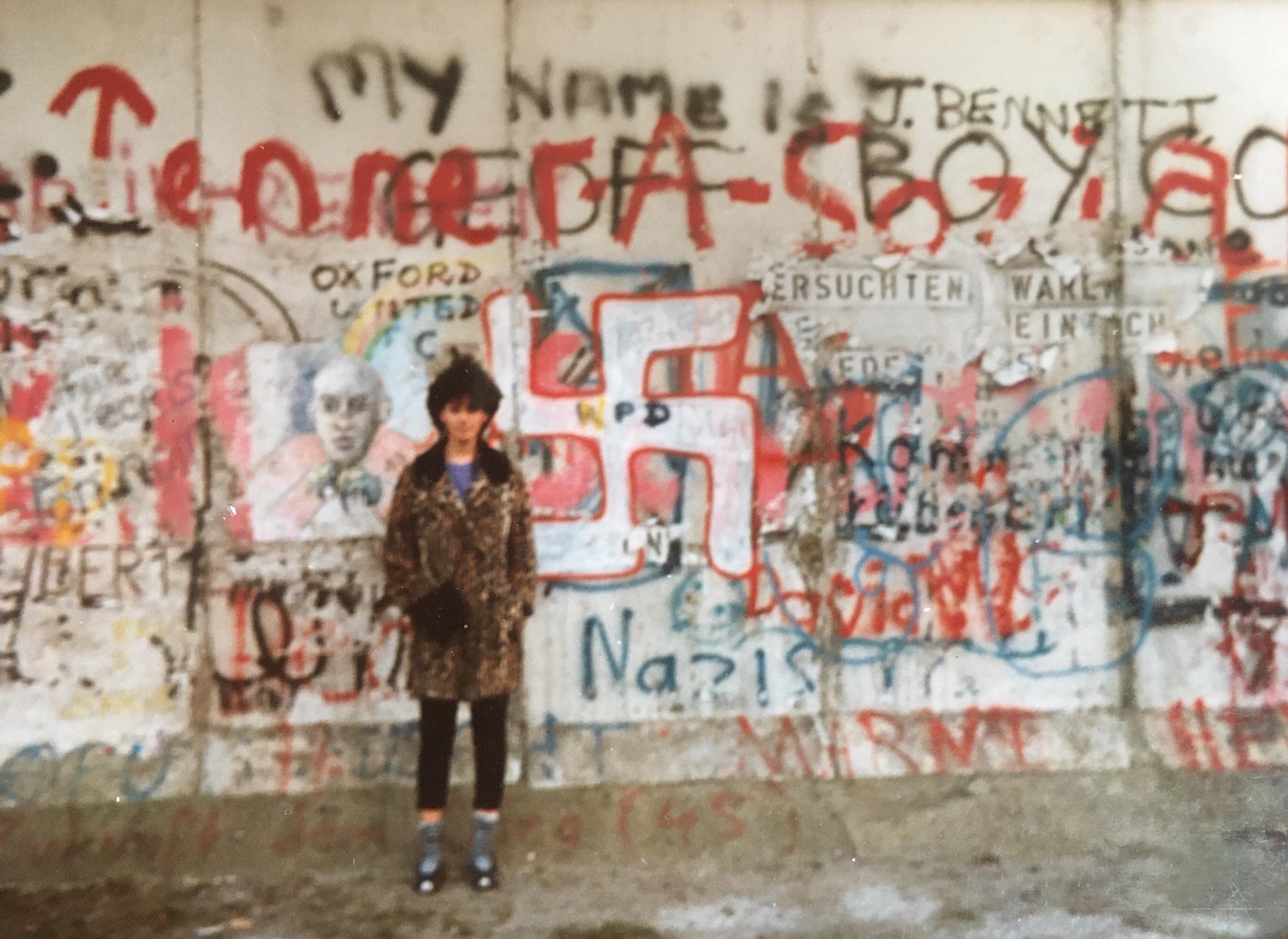

Working with other people in all mediums in theatre, including the possibility for vast stage sets, has proved to be perfect for my gregarious side, whilst the need to be solitary is fulfilled by painting. During the 80’s, over several summers, I was invited to attend ‘Symposiums’ in the then Czechoslovakia. These took the form of a variety of Artists living and working together, perhaps in farm outbuildings, over a month or so. This meant that around a meal together in the evening, the day's work was discussed, and it proved to be the perfect way to ‘immerse’.

︎︎︎︎︎︎

Exorcising the Totalitarian or Life in Bohemian paradise

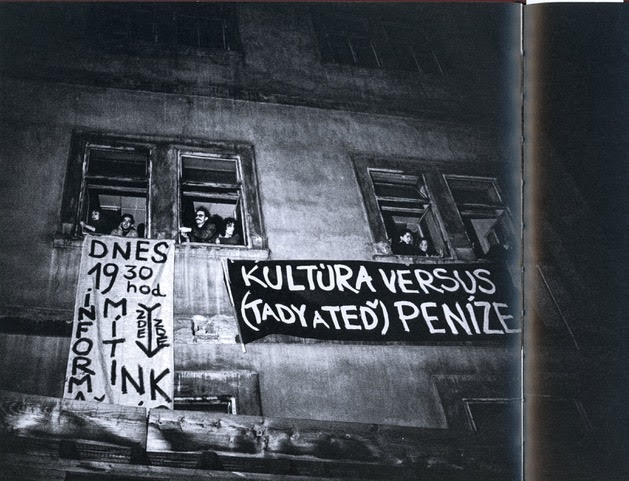

By the time of ‘The Velvet Revolution’ in 1989, the people that I had met, invited me to join in running an Art Foundation, set up to harness all the creative energy which had been blocked by the Totalitarian system of the previous 40 years. Suddenly, I found myself in the most energetic and adventurous situation imaginable, where each day for several years, something extraordinary happened.

︎︎︎

The government had also given us a ‘palace’ in the centre of Prague which had been the headquarters of both the Communist and Gestapo before them. We moved in and set about exorcising any remnants of the building's recent history, by producing theatre, music, painting, sculpture etc.

The government had also given us a ‘palace’ in the centre of Prague which had been the headquarters of both the Communist and Gestapo before them. We moved in and set about exorcising any remnants of the building's recent history, by producing theatre, music, painting, sculpture etc.

Our first big festival was called ‘The Totalitarian Zone’, based in a 5,000 sq. metre bunker, built to support an enormous statue of Stalin and his Comrades, and situated in the park overlooking Prague. Due to the support of the new government, who on the whole were artists themselves, we were able to bring artists from all over the world to construct their work within this space into which the rubble of the Stalin sculpture had crumbled. Vaclav Havel, the president, opened a radio station for us, at the site, through which we could collect all the materials that had been requested to create the installations. Needless to say, alongside helping people to facilitate their artwork, I was myself constructing work of my own.

The government had also given us a ‘palace’ in the centre of Prague which had been the headquarters of both the Communist and Gestapo before them. We moved in and set about exorcising any remnants of the building's recent history, by producing theatre, music, painting, sculpture etc. At 8 in the morning of the first show in the courtyard gallery, which happened to be my work, the president called by to congratulate me on his way to the castle. This really was life in Bohemian paradise!

Meanwhile, for me coming from further west, living in what was to become The Czech Republic, was incredibly cheap, to the point where, for several years, I could rent a space for around £5 a month, fill it with new work, and when there was no further wall space, lock the door and move on to another rental! Within a year, we had also been given an old theatre building in the centre of Prague, The Roxy, which after some time, Linharts’ Foundation opened the doors of this raw and inspiring space, to work with a wide variety of people from different parts of the world. This was yet another opportunity for me to make large scale pieces. Due to the lack of many regulations in the early 90’s, we were able to utilise a park by a lake, a castle where Mozart had performed, an asylum, churches, botanical gardens, indeed anywhere we chose for the pursuit of Art, even to the point of painting a tank on a podium, pink!

︎︎︎︎︎︎

A view towards the world

We continued with the symposiums, and one summer a visiting art critic from Moscow , Vitaly ——, invited me to produce a show in the Russian countryside, to exhibit in Moscow. In 1990, also exhibiting was Joseph Boeuys , and since at that time, I could, as a visiting artist, be perceived as comparable in stature, I was also given free range to explore all the work in the basement at The Hermitage in St. Petersburg. From there I visited a village which housed many artists who had against all odds, managed to continue to make painting and sculpture outside of the prescribed notion of art. They welcomed me in their enthusiasm to speak about art, and again I realised that outside of a commercial system, the authenticity of the art remained paramount.

Since much of my exhibition in Moscow was composed from materials found there, the show was spoken about, in terms of the natural pathos that I demonstrated for Russia. Perhaps the legacy from my family migrating from the soviet union 100 years before, prevailed. Before leaving, Vitaly asked me if I would give him two of my pieces for him to exhibit alongside, amongst others, Malevich and Kandinsky. Again illustrious company! The rest of the 30 or so paintings and sculptures remained in the safekeeping of the director of The BundesBank, where they may still be.

That same year, 13 of us were asked to travel to San Francisco, to create an exhibition in-situ, which was by this time, my preferred method of making work. Then in San Diego, I was given a concrete support (for the flyover) on which to make a mural in Chicano park. My fear was that up to this point, only Mexicans had made the paintings in this park and they were all highly political. All was saved, by the fact that my abstract work was construed as a representation of a mushroom cloud!

︎︎︎

I realised that outside of a commercial system, the authenticity of the art remained paramount.

I realised that outside of a commercial system, the authenticity of the art remained paramount.

Back in Prague, we started to organise the next festival ‘Light Removes Darkness’, with a nod to the Dalai Lama, as we moved beyond totalitarianism. Contributors were requested to make installations with their own light source, and the show was stolen on the opening, by a work produced the night before which the security people at the door of ‘Stalin's bunker’ had impulsively constructed. My contribution was set at the end of the final long tunnels, where stone slabs and wall surfaces were painted to give the impression of 2D in 3D, in which I gave a rare performance with fire and violin.

Over the following 7 years, I continued to make paintings in a wide variety of spaces and places, including Austria, France, Italy, Peru and Czech Republic. Always writing, mostly in dry technical terms, about the artwork as it was produced, one day as I sat on a hillside in Prague, the following stream of consciousness arose. With that in mind, I set about evolving a process which I could utilise for encouraging ‘students’ to make abstract works through true response and free from qualitative judgement. Sculpting with the blind and constructing with people from the asylum, proved that when you provide a wide variety of materials and a process through which to use them, the results can surprise even the maker.

In 1996, with the idea that Madagascar contained more species than the whole world put together, I set out equipped with a suitcase of small unstretched canvases. Although the 3 months there meant that the paintings could be done, the heavy rains prevented most exploration and I did not even come across a lemur. Then came the time to go back to an English speaking country, to live by the sea.

︎︎︎︎︎︎

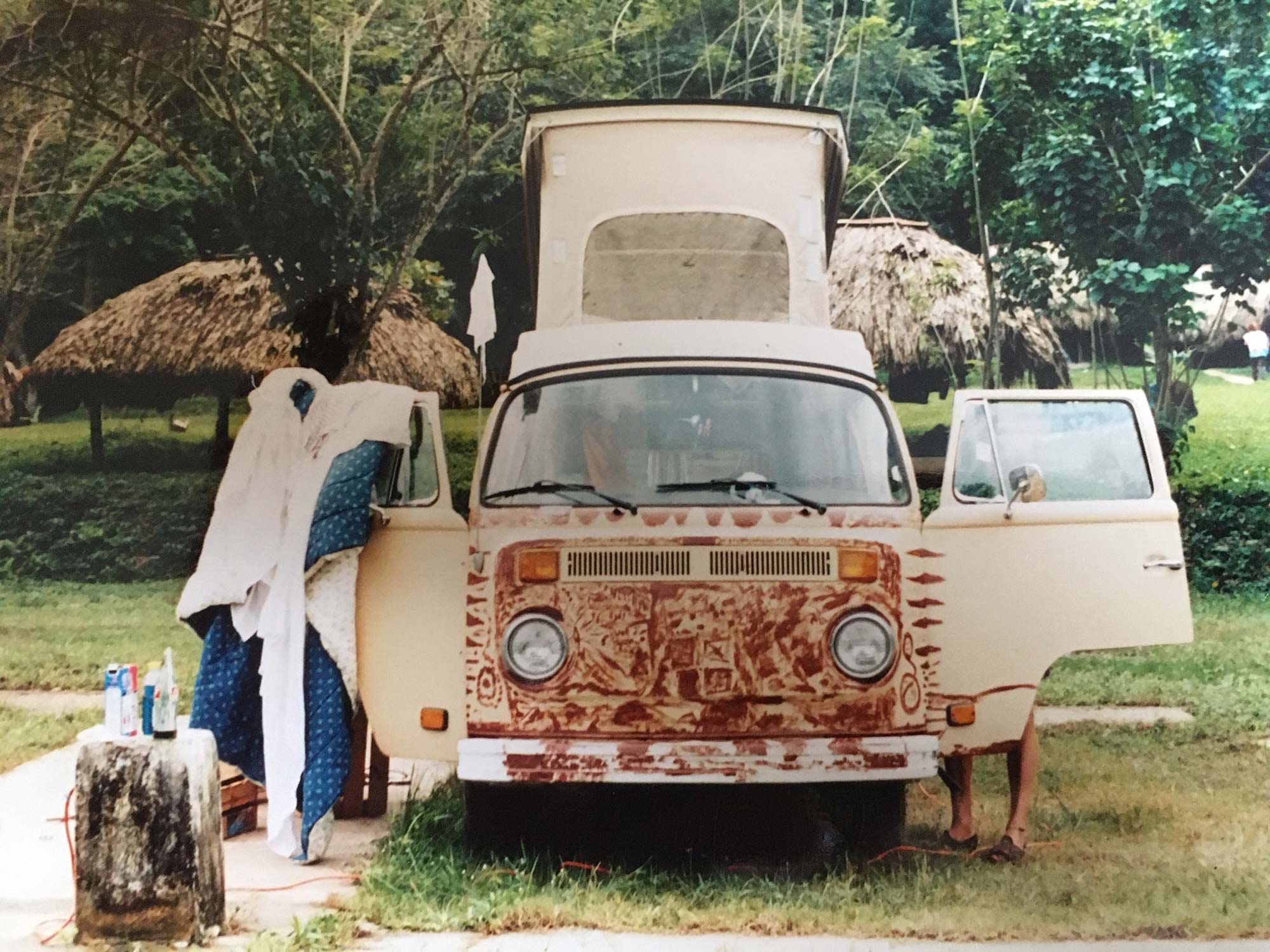

Back with a van and a dog

From London, with a van and a dog, I decided to tour the whole coast of Britain. My first stop, visiting my closest friend, was Lyme Regis in Dorset, and I quickly realised that I wasn't going to find much better than that! That year, I was delighted to have a large canvas selected to hang in the collection at Kensington and Chelsea Hospital. An unused Georgian X library in Bridport, Dorset, served as the perfect venue for a retrospective ‘Time Takes a Cigarette’ in 1998. Around a hundred canvases were luckily curated to hang in the many rooms. This was followed by a show in London, ‘Sunshine I’m only dreaming’, which consisted of the new work that I had been doing since back in England.

In 2002, 16 large stretched canvases only just survived a fire in my apartment, and they were then recreated for an exhibition ‘Into The Frying Pan’. The challenge to transform these destroyed surfaces into new pieces, led me to realise that there was a value in working from something that is initially disagreeable.

For many years, I had discussed with the photographer, Katia Marsh, the difference between the abstract and abstraction, until we finally decided in 2004 to exhibit works in our own mediums around the subject. In Lyme Regis, I started to reconstruct a glass roofed warehouse space as a studio, only to be turfed out after 9 months, by a landlord who wanted it for himself. That led me to the attic space at the Mill, which due to a reduction in size of my surroundings, I began to concentrate on small works ‘Out Of The Rectangle’.

Adhering to the power of synchronicity, my aim for 81 pieces finally revealed to me that my whole practice was really only about how many possible ways that I could find to make an abstract work. This work formed part of my exhibition at the adventurous Gallery Terracina in Exeter. It was here that I discovered that contrary to what I held felt about public speaking up to this point, I actually enjoyed talking in reference to my exhibits.

In 2007, the challenge arose to ‘decorate’ the vast warehouse spaces of the company ‘And so To Bed’, with my works. The interest here was to see so many paintings in a setting that was made to resemble a fully furnished stately home. In 2008, I was given permission to stretch a canvas covering the whole side of a two storey building. For this I invited all in the area to bring anything other than biodegradables, that they were throwing out. These, I attached to the canvas to create ‘a drawing’ and using a compressor, I sprayed the whole with grey acrylic. Once the objects were removed, their remaining ‘shadow’ served as the bases for the final worked composition. This is one method that I use to ‘animate’ the picture plane with only partly predictable mark making, rendering an informal linear juxtaposition, to which the composition evolves through my reaction.‘

Out of The Rectangle’ followed in 2010 at The Redgate Gallery, London, where many shaped and generally fragile 2D pieces, were composed by amalgamating found objects. Here, the necessity was to ‘free’ on first glance the 3D items from their original identity, so that their properties served to create a rhythmic composition across the chosen surface. This was built upon to become the next show ‘Debris in 2D’.

︎︎︎︎︎︎

‘The Jam Factory’ and ‘Stray Dog Productions’

By now my studio was ‘The Jam Factory’, a 5,000 sq. foot barn on the Dorset /Devon border. The danger was that it would very quickly be filled with a multitude of art. All events produced in and out of The Factory, that involved others becomes a ‘Stray Dog Production’, the name appropriated from a group in Stalinist Russia who managed against all odds to keep their underground theatre open for samestat poets etc. Throughout these years at the Jam Factory, there have been annual Theatre events, where I have directed Sinistra Theatre company, in a variety of Absurdist performance pieces. This stretches me to bring words, sound, movement, music, costume, and stage set into my repertoire, allowing the further pleasure of literary research.Due to the realisation of my indebtedness to certain artists from the past, whom I considered had given me ‘new freedoms’, I decided to make 19 works as a Homage to them. This became ‘19+1’, with the one referring to all the ‘others’ not mentioned and perhaps ultimately to a work produced beyond homage to anyone. These are hefty ‘slabs’ of rectangles, each of which brings in an element of those artists, rather than an imitation. They employ objects alongside the painted mark, the latter of which serves to provide the possibility for a change in focus through such detailing.

︎︎︎︎︎︎

The Great and The Small

In 2013, the town of Lyme Regis provided the opportunity to build a project around one of the exhibits in their museum. I chose a maquette of a landmass which contained a signpost, one arm of which said ‘Lyme Regis’ whilst the other, ‘Annapurna, Himalayas, 4,500 miles’. The fascinating element was that this denoted the seam of ‘Blue Lias’ rock that ran from Dorset, only to end in The Himalayas. My premise was that I wished to prove through artistic pursuits, connections that also may exist above ground, between the two places. For this, The Arts Council provided a grant which enabled me to take a photographer, a theatre director and in her own words, A Stray Dog. Hopefully, between us, from this hugely adventurous and stimulating trip, we were able to demonstrate in the exhibition ‘The Great and The Small’, that indeed, many connections do exist, even over such distances, both geographically and culturally. My work in this instance branched into more sculptural pieces, influenced by the Buddhist practices of the area, providing a rare foray into ‘meaning and narrative’, with still nonetheless, an abstract aesthetic.︎︎︎︎︎︎

Ongoing synchronicity

Under the stray Dog banner, www.365-moments.com was formed to provide an incentive for people to find a daily focus for their creativity. On a 4 month ‘world’ trip in 2014/15, in order to comply with my 365 regulations, I set about ‘Project 88’. For this, by noon every day, I selected through various means, a ‘word’ for the day. At times the word reflected perhaps an aspect (history/ geography/ society) of the place that I was visiting, or from something I had read. After some time, the word generally arose from some need to concentrate on something of an abstract nature. Once the word ‘happened’, it would feel that it could only be that particular one I would then relate that word to 7 different ‘subjects’ throughout the day:-

something learnt or witnessed.

-

someone encountered where there was even a momentary connection.

-

something absurd or humorous.

-

some synchronicity.

-

an object.

-

a sound / music/ smell/ taste, intrinsic to the place.

- impulse....by way of creating a postcard sized collage.

︎︎︎

I discovered in India that when people are presented with seductive materials and a specific process, many are enthusiastic to make painting without being necessarily concerned about making ‘art’ specifically.

I discovered in India that when people are presented with seductive materials and a specific process, many are enthusiastic to make painting without being necessarily concerned about making ‘art’ specifically.

By 2014, it became essential to try to ‘Take Stock’ of what was now a vast amount of output in my studio, assessing the work as it came out of the many storage places. In deciding on works that did not reach their full potential, I then chose to attempt their transformation, failure of which led them to the bonfire.

2016, proved to be the time ’To Get a Grip’, and my finished works went up for sale in London and Dorset. I discovered in India that when people are presented with seductive materials and a specific process, many are enthusiastic to make painting without being necessarily concerned about making ‘art’ specifically. In 2016, I decided to see if the same applied to the refugees, in the Calais ‘Jungle’ at the time. Indeed, the interest to come and use materials was overwhelming, and over 70 works now form part of a touring exhibition.

This was repeated in Athens in May 2017, and there many works of up to 3 metres formed an outdoor exhibition. In utilising cones of henna to draw with, and water to dilute and spread the henna to differing degrees, the resulting drawings/ paintings have an intrinsic beauty in direct relation to the material. To Athens, I also took 12 x 3 metre hangings, with the canvas rectangles prepared with differing linear structures and white mark making to integrate each surface plane. In connection with the ‘Documenta 14’ title ‘Learning From Athens’, one of the 12 Olympian immortals was bequeathed to each work, by people selecting from a 3 word summary of characteristics belonging to each.

The finished work, with my abstract painting on one side and participants’ overlay paintings on the other, will form a 8 metre wide circle, a Pantheon within which actors will perform. This will include a 13th hanging as part of ‘Bakers Dozen’, with the 13th representing everything else or indeed nothing!